In recent years I’ve developed an interest in mechanical watches and how the aesthetic and product design decisions, made over a hundred years ago, have defined and informed wrist watch design today. In today’s digital world I find myself drawn to these physical and tactile things, hand-finished and steeped in heritage and history.

There’s a history of watches where I work at Arnold Clark Digital. In fact, high-value sales jobs and nice mechanical timepieces tend to go hand-in-hand. Spending a lot of money on a watch can seem strange to most people, especially when your phone or a £15 Casio watch can do a better job of keeping time. But there’s a lot more to the world of mechanical timepieces than simply telling the time.

Company folklore here is that, in the past, loyal or high-performing staff were rewarded with Rolex Submariners or other similar expensive watches. When I’ve visited branches and chatted to the Product Consultants and branch managers, I always spot some interesting timepieces. Since we started filming and sharing the director’s presentations on our employee platform (ACE), I’ve found myself pausing the video, zooming in on the director’s wrists and identifying some of the most sought-after watches in the world.

I thought it might be fun to examine the cutting-edge horological product design of the 1970s and see what lessons we can learn and apply to UX and digital product design today.

We’re going to look at a specific area of technology and class of watch. The dive watch or simply ‘diver’.

First, a bit about saturation diving

Saturation diving was introduced in the late 1960s to help reduce the total decompression time that divers had to endure. In this method of deep sea diving, the divers can spend weeks working at incredible depths in order to build underwater infrastructure, maintain gas pipes, deconstruct oil sites and much more. During this time the divers will live in a pressurised environment so that they can conduct their dangerous and specialist work, lots of times, without having to go through decompression over and over.

Decompression

Quick note if you don’t know, when humans spend a long time under water breathing pressurised air, gasses like Helium and Nitrogen dissolve into their blood and stay compressed because of the weight of the water around them. If they were to come up to the surface quickly, the gasses in their blood would decompress and form bubbles inside their body, resulting in a quick and painful death. Check out the hour-long documentary Last Breath on Netflix to get a peek into the world of saturation diving.

Humans aren’t the only things affected by quickly decompressing gasses. Because the divers are breathing pressurised air rich in Helium (which boasts the smallest natural gas particle in the world), these atoms find their way into the diver’s watches. Like humans, this isn’t an issue until decompression when the gas quickly expands and pops the crystal off the front of the watch with a tiny explosion.

There was a clear product problem to be solved and two main players racing to solve it, Rolex and Omega.

Try to find the real problem

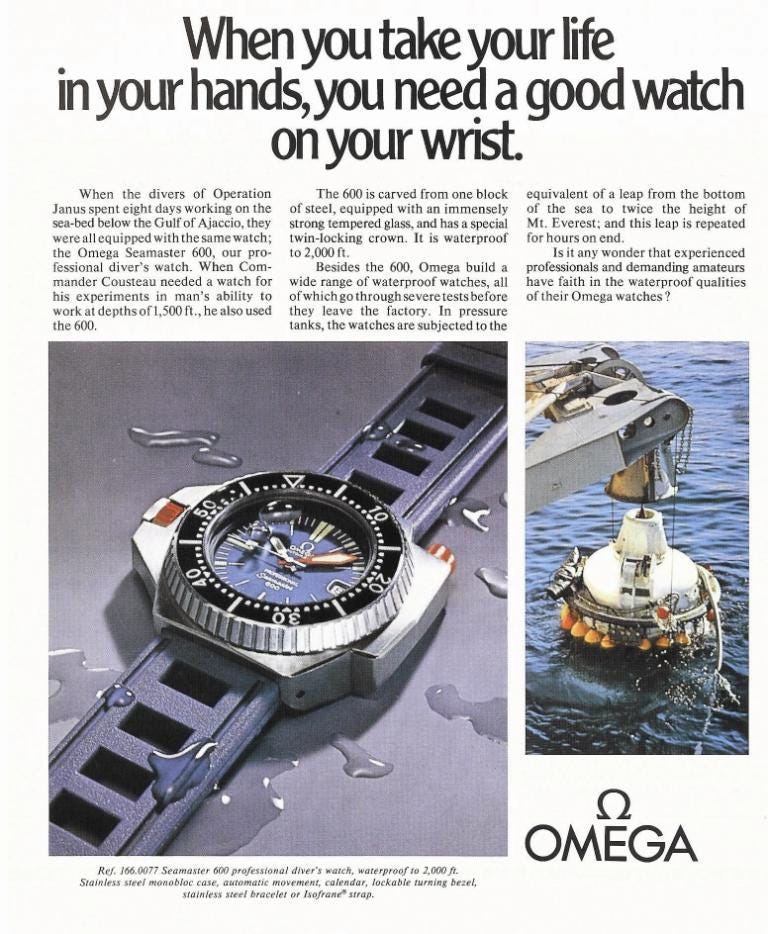

Omega, a big name in the professional dive watch space, went straight to work on their new watch, The Seamaster 600, also known as the Plongeur Professional (Ploprof).

Because the issue was identified as Helium escaping too quickly, Omega thought that the best solution to the problem was to develop a watch with a case made of steel, so thick and impenetrable, that no helium could even get in, let alone escape. Makes sense, right? Or does it? What might Omega have got wrong running with this solution, or how could they have solved the problem more efficiently?

In Thinking Fast and Slow, Daniel Kahneman identifies the two thought systems that we humans have. There’s ‘System One’, the instant, unconscious, automatic, emotional and intuitive brain. Then there’s ‘System Two’, the slower, conscious, rational, reasoning and deliberate brain. Omega’s solution looks like intuitive thinking and a System One response, the obvious answer. They likely wanted to move quickly to offer the first dive watch capable of withstanding the rigours of saturation diving and because of this, didn’t deeply explore other ideas.

If they had identified that their first solution had System One in the driving seat and spent more time on ideation, then they may have struck upon a much leaner, quicker and more efficient solution, like Rolex did.

Lean thinking and innovation

In any creative work, it’s important to ideate beyond the obvious solution, you will likely uncover a better one by pushing yourself to explore different ideas.

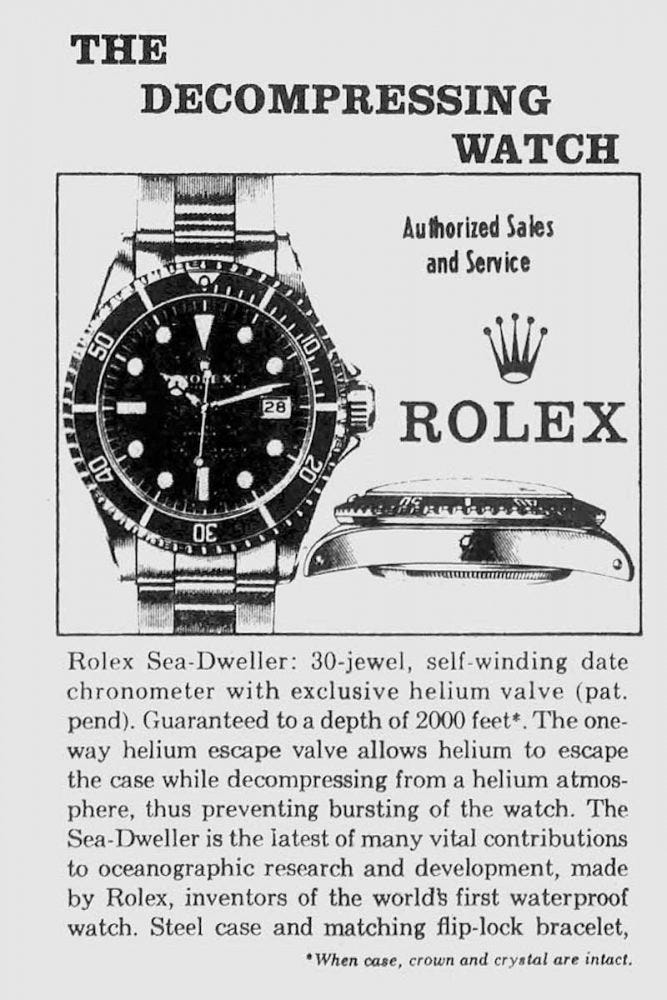

Rolex worked out that it was ok to let Helium get into the watch case as long as it could escape safely. This approach required the toughening up of some of the components from their existing Submariner dive watch. They also introduced a Helium escape valve that the diver could open to let the offending gasses escape safely. With this innovation, the Rolex Sea Dweller was born.

By digging deeper, Rolex were able to get their solution to market quicker and beat Omega by years. Being first-to-market in this space was important and it helped solidify Rolex’s name in the professional dive watch space.

In any creative work, it’s important to ideate beyond the obvious solution, it’s likely that you will uncover a better one by pushing yourself to explore different ideas.

What can we learn from Omega’s failure and Rolex’s success?

There are valuable lessons in this story and a chance to remind ourselves of the important parts of the creative process that we already know, but are guilty of neglecting.

1. Keep your thinking lean

Rolex took the opportunity to build on and adapt technology and parts they already had, rather than engineer something brand new. We can apply this type of lean thinking to almost every part of the product design process.

There are always things that can be done in less time with less effort that achieve the same or a better outcome, we only have to look for them. Here are some tools that we can use to uncover these gems.

There are always things that can be done in less time with less effort that achieve the same or a better outcome, we only have to look for them

Five Whys

As designers we get it, our stakeholders, colleagues and peers will naturally go to solution thinking, this is just human nature and something even designers have to catch themselves doing. The skill is in watching for this and refocusing on the problem. As they say at Intercom Start with the problem.

Five whys is a powerful tool for refocusing on the problem. It’s very simple. Your stakeholder comes to you with “I’d like you to build [insert feature here]. You come back to them with “Why?”. Then for every answer you ask ‘why’ again, until you’ve done it five times. You can feel like a toddler who’s just learned the word ‘why’, but it works.

Assumptions mapping

Assumptions mapping can help you and your team identify the unknowns and the leaps of faith you’re making in the areas of your product’s…

- Desirability: do customers want it?

- Feasibility: can we build it?

- Viability: should we build it?

Conversations, where assumptions and leaps of faith were noted and discussed, could have stopped Omega from dedicating years to the engineering of the ProPlof.

Assumptions Mapping — Mahima Pushkarna

6-up Sketching or Crazy 8s

Whether it’s 6-up or Crazy 8s, the concept is simple, you have a certain amount of time to sketch a certain amount of ideas for your solution. Your first idea is rarely your best idea.

Neurologist David Eagleman says “The key to innovation is to distrust the first answer and to send it back. Send the answer back so you’re getting something else out of that rich network that’s already in there.”

Using sketching to get your ideas out of your head and on to paper does something magical. It lets you move on from that first idea which is often hard to shake off. This helps you to think beyond the obvious and truly innovate.

‘How Might We?’ Questions

After the discovery phase of a project or after research on your existing product has been carried out, hopefully, you will have a raft of insights to address. How Might We questions are an amazing way to make sure you’re ideating on the real problem. But be careful, because it’s easy to write your own bias and your System One solution into the questions. Here are examples of how these questions could have been used well and used poorly at Omega.

Problem: Escaping gasses are breaking the watch during decompression. HMW (Poor): How might we stop gasses getting into the watch case? HMW (Good): How might we stop escaping gasses causing damage to the watch?

How Might We Questions — Nielson Norman Group

How Might We questions are an amazing way to make sure you’re ideating on the real problem. But be careful, because it’s easy to write your own bias and your system one solution into the questions

2. If you can, be first, but not at all costs

Omega had much better technology and engineering than Rolex did, but this didn’t matter. Rolex’s leaner and simpler engineering strategy was indistinguishable from Omega’s to the customer. The outcome was the same, a watch that withstood the rigours of saturation diving. The difference was that Rolex was first-to-market with their product and galvanised their name as innovators and experts in this niche market. By the time Omega launched the PloProf, Rolex’s Sea Dweller was well established as the saturation dive watch for professionals.

We see this all the time with digital products and services. Being first with a decent (not perfect) offering often means your product or brand becomes synonymous with that space.

3: Jacobs law of UX

Rolex’s new Sea Dweller looked like a dive watch and had “Rolex DNA”, i.e it looked how people expected a Rolex dive watch to look. Omega’s PloProf, however, was a wild departure from anything that had ever been seen in this space before.

Jacobs law of UX says that people expect things to function how other similar products function. Too much deviation from this can be confusing, frustrating and off-putting for people.

People expect things to function how other similar products function. Too much deviation from this can be confusing, frustrating and off-putting for people

4. Slow down to speed up

In Omega’s apparent rush to be first-to-market, it’s likely that they spent less time ideating on the solution and went quickly to engineering without properly exploring leaner options. This choice, while on the surface appears to be the faster one, ended up costing them years. Omega later used Rolex’s innovation and introduced a Helium escape valve on their Seamaster and the PloProf was rendered irrelevant.

You might have heard the advice or phrase ‘slow down to speed up’ in the world of product design. This is very often overlooked advice, but can pay off in big ways. Yes, fast is good and speed is one of the most valuable qualities of a product team, but it’s crucial that we take time not only to make sure we’re building the thing right but more importantly that we’re building the right thing.

Yes, fast is good and speed is one of the most valuable qualities of a product team, but it’s crucial that we take time not only to make sure we’re building the thing right but more importantly that we’re building the right thing

5. No one wants to use your app and no one cares about your tech

People don’t want to search for taxis on Uber, they want to get somewhere. No one wants to look for places to stay on AirBnb, they want to enjoy their holiday in nice accommodation. Our customers don’t want to visit Arnoldclark.com, they want to find their next car, book their service, or find relevant information.

Omega may have had technically superior engineering than Rolex, but customers don’t care about the tech as long as it works well. Professional saturation divers, who needed a decompression-proof, 600m water resistance watch, chose the one that was available that did the job.

Us designers and engineers are the most guilty of this. Your customer doesn’t care about how abstracted your code is, how easy it is to maintain, how tidy and well-formatted it is or whether you’ve spent two days or two minutes refactoring it. Likewise, users don’t care if you’ve designed a perfect vertical rhythm, where all the type sits perfectly on the baseline grid or if there are intricate animations and transitions. All they care about is that the thing does what it’s supposed to do and does it well.

Don’t build your own Ploprof

While the Ploprof has since become a curio and a collector’s item, the things we’ve learnt from a digital product design perspective are huge. If we have a relentless focus on defining the problem we’re solving and persistently returning to it during our conversations, creative ideation and the physical building of the product then we can avoid falling into the same traps that Omega did. If we can start with and regularly refocus on the problem whilst using the vast array of tools at our disposal to ideate beyond the obvious and beyond the System One then we’re most of the way there. I encourage you to look at your own work from your simple user flows down to the small UI patterns you use and ask whether you’ve explored deep enough and if you’ve missed an opportunity to innovate.